To look at this blog, you’d think I hadn’t read a book since February. That isn’t true, but it’s close enough to being true that I really have to find a convenient time warp where I can catch up on reading without having to cut back on anything else. For the record, though, I’ve read the following (excluding books that I’ve completely forgotten I read):

Revival – Stephen King

Electricity: Not necessarily our friend.

Stephen King works in the modern tradition of bestselling horror, which to my mind began with Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, though you could track it back further to some of Richard Matheson’s early, lower-profile novels like I Am Legend. But it was Levin’s runaway bestseller and the movie that followed that seemed to break the dam open and led directly into William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, which led into…a long line of Stephen King novels that’s continued from Carrie through whatever his most recent book is. (It’s hard to keep up.) The modern horror tradition places a strong emphasis on settings that are familiar almost to the point of banality, which the author uses as a means of creating a suspension of belief so profound that you’ll buy into whatever unexpected curve ball he or she pitches out of their word processor to shatter the banality into terrifying shards, like Rosemary’s neighbors turning out to be a coven of Satan worshippers or Carrie turning out to have telekinetic powers brought on by her first menstrual period.

Revival, however, is King’s homage to the older generation of horror writers that he (and I) grew up reading from an age when we were young enough to accept outre settings that were nothing like the world we lived in. It’s specifically an homage to, and in many ways an updating of, Arthur Machen’s 1894 novella “The Great God Pan,” which is about individuals who have managed to glimpse the true nature of reality that lurks behind the shallow scrim of the mundane, a reality so different and so much more terrifying than the world they thought they lived in that it drives them mad when they discover it.

King, as is often his wont, carries the story’s setup to such verbose extremes that I began to worry that he was losing track of the horror element that Machen had been considerably more focused on. Those worries turned out to be needless. Almost every scene in Revival pays off eventually and turns out to be essential to what follows. Whether what follows is worth the wait is a matter of taste. The glimpse of the reality beyond reality at the end is indeed terrifying and I find that it’s come to haunt me even more in retrospect than it did while I was reading it. To accept it, though, it’s necessary to have your belief suspended so tautly that nothing can possibly yank it down. Thankfully, mine was up to the challenge. The novel threatens at times to become a slog, as you learn more about the relentlessly ordinary protagonist than you really want to know, but it never quite bogs down completely. Then again, I’m a long-time fan of old-time horror, so nothing was going to prevent me from getting to King’s take on it. And I’m glad I waded through the sometimes interminable exposition required to get there.

This, I should note, is one of those first-person stories where the most interesting and significant character isn’t the narrator but a secondary character who wanders in and out of the narrator’s life. (H.P. Lovecraft’s classic horror novella “The Thing on the Doorstep” is similar.) And if there’s anywhere that the book falters it’s in the believability of that character, who crawls farther out on a limb of eccentricity every time we meet him. There are moments toward the end when it feels like King is fighting to keep him just grounded enough that the reader’s acceptance of him as a real person won’t turn into a hot air balloon and float away, but it’s touch and go for a while. In the end King pulls it off, but by that time I was so thrilled to see him finally get to the story’s ultimate revelation that I was ready to believe anything King told me.

The title, incidentally, has multiple meanings, one of which is simply King’s revival of old-school horror. I’ll leave it to potential readers to discover the others. (There are at least two more.)

The Brilliance Trilogy — Marcus Sakey

Book three of the Brilliance Trilogy

I reviewed the first two books of this trilogy, Brilliance and A Better World, in earlier installments of this blog. To summarize: I loved them. A lot. But I reread them in preparation for the third book, Written in Fire, and I was thrilled all over again. Sakey pulls off the whole Brilliance enterprise — the adverb is unavoidable — brilliantly.

Collectively, the series is about a civil war between genius-level mutants called brilliants and the ordinary humans who feel like they can no longer keep up with their intellectual superiors. I was impressed not only by Sakey’s believable depiction of the mutants but by the way he gives each of the three books its own slow-rising plot arc, with each one not fully starting to grip until about halfway through, at which point they become impossible to put down. He manages to sustain this through the entire three-book serial arc as well, except the peak comes in the final third, which is a hat trick that I wish other writers of trilogies (see below) could pull off as deftly.

There’s a touch of deus ex machina in the way the final novel is resolved, with Sakey setting the resolution up in advance but not in a way that’s totally believably in retrospect, letting everything hang on a moment of hubristic boasting by one of the characters that I think the character would have been savvy enough to avoid. But everything else about the third novel is so compelling that I’m more than willing to forgive this lapse. Sakey’s mutants are fascinating, but the one that stands out is the frighteningly vivid Soren, a sympathetic bad guy who sees time move 11 times more slowly than other human beings, even other mutants, do, which makes him horrifyingly dangerous, because he’s thinking 11 times more rapidly than the hero, but also isolates him from his peers in a way that leaves him open to manipulation by the book’s real villain, who orchestrates much of the apocalyptic chaos of the final scenes through the charismatic way he makes people like Soren think that he actually cares about them even while he uses them to achieve his own ends.

Sakey’s greatest strength is that he makes every character’s motivations feel genuine and in many cases sympathetic, even when what they’re motivated to do is appallingly wrongheaded. He leaves a hook at the end that could be used for a sequel, though Sakey says he has no intention of writing one. However, he’s been letting other writers play with his carefully constructed world and, though I haven’t read any of the non-Sakey spin-offs, I wouldn’t be surprised if some of them don’t continue where this novel leaves off.

I’m not sure I want to revisit this world, though. Sakey does such a satisfying job of telling the story that I’m worried I might see some lesser writer mucking it up. For all intents and purposes the story has now been told and told well, and that’s how I want to remember it.

The 5th Wave Trilogy – Rick Yancey

From the sublime to the tedious.

When I reviewed the first, eponymous novel in this series I raved about it. Yancey’s characters were complex, their relationships were compelling, their moments of self-revelation felt meaningful and Yancey’s writing frequently rose to the level of unexpected poetry. When I reread it to bone up for the rest of the series the poetry was still there but the rest seemed a bit flat, probably because I remembered too many unexpected twists from my first time through. It still stands pretty well as a complete work, though, and I’m sad to report that, except for the threads Yancey leaves dangling at the end, it should have remained a standalone experience.

The Infinite Sea, the second book of the trilogy, tells two stories, each of which could have been wrapped up in a couple of chapters instead of stretched out to half the length of a novel. Much of the time Yancey seems to be padding his way toward book three just so he can do the full triple-book treatment that seems to be required now in YA fantasy and science fiction whether the stories merits it or not. As much as I enjoyed them, I blame the Hunger Games novels (or perhaps the Twilight series, which I haven’t read) for that. There are entire scenes in The Infinite Sea that feel like they’ve gone on forever even when you realize that Yancey is going to make them go on even longer and if I hadn’t been as determined to finish this trilogy as I’d been to finish Sakey’s, I probably would have put the book down partway through (virtually speaking, because it’s on my Kindle, which I’d still have to pick back up to read something else) and moved on to more promising pastures. But I figured the third novel had to be better.

And it is. The Last Star picks back up with characters from the first book who vanish for long sections of the second and starts telling a real story again, but it still feels padded with unnecessary dialog and scenes that loop back so frequently to the same repetitive arguments that I wanted to tell Yancey just to get it over with (or possibly shoot me) to put me out of my misery. He finally does — get it over with, not shoot me — and the fact that I can’t even remember how it ended probably says more about how weary of the book I was by that point than any specific criticism I could make — if I could remember enough to be critical. I do remember that the climax was designed to bring tears to my eyes, but I was too sick of the characters by then to muster even a slight layer of optical mist over whatever it was that happened to them.

The 5th Wave should have been at most a duology and I’m not sure Yancey shouldn’t just have made the first novel longer and wrapped it all up there. Still, the first novel remains worth reading, though you might want to take a pass on the sequels and imagine your own resolution. It’ll probably be better than the one Yancey supplies. Or at least briefer.

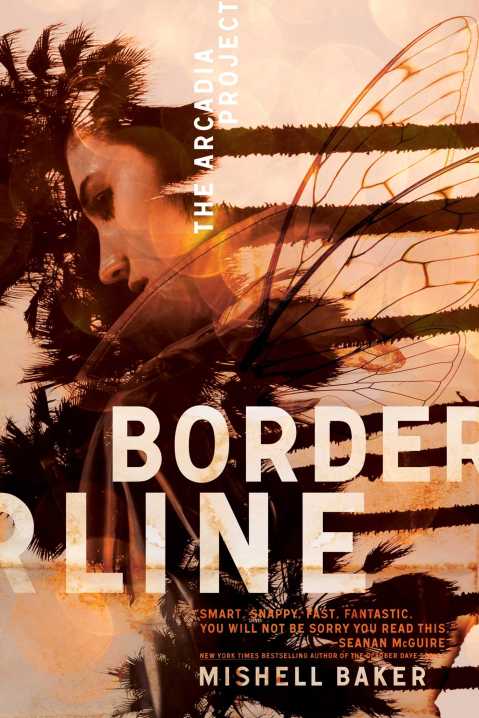

Borderline (The Arcadia Project) – Mishell Baker

The borderline between well-written characters and well-worn premises.

This is the book I’m reading now, in bits and pieces of snatched time, mostly before I fall asleep at night. It has a fascinating beginning setting up a fascinating heroine that unfortunately leads into a well-written but overly familiar detective procedural with an interesting if not entirely original fantasy overlay that doesn’t quite lift it above the pedestrian level of detective procedurals in general. But Baker’s writing is excellent, her wit sharp and lively, and I’ll read it through to the end. It’s not giving me the sort of thrill I got out of Sakey’s frequently noirish take on mutantkind, but maybe it’s unreasonable to demand that every book hit notes quite that high.

As with King’s Revival, the title has more than one meaning, though the more interesting one is that the protagonist suffers from borderline personality disorder. This is the main element that lifts the novel above the level of standard fantasy noir, but as the book goes on her psychological diagnosis begins to seem more and more like an excuse for the sort of snarky first-person narration that detective fiction writers have been using since Raymond Chandler published The Big Sleep. The book’s depictions of Los Angeles and the film industry are quite good, though, and at this point are holding my attention more than the heroine’s mental disorder or the physical problems resulting from a suicide attempt that occurred before the novel begins. (Both of her legs are prosthetic, a detail that’s handled so believably that I wonder if author Baker has personal experience with it or is just really good at research.)

If the novel surprises me by transcending its fairly predictable underpinnings, I’ll write about it again later. Otherwise, I’ll only say that the novel is worth reading if you don’t have anything more compelling at hand or if you just like procedurals, a form of fiction I used to read by the bucketful. At some point, though, I think my bucket overflowed. Maybe yours hasn’t yet.